In the mix with all the other craziness that is going on, we still have a presidential primary ongoing—Bernie Sanders has clearly opted not to drop out, given that he participated in an online campaign event on March 22, and his campaign has expressed interest in participating in an April debate.

Thus, the beat goes on. But the average person probably isn’t aware of what’s been playing out with the primary, due to the COVID-19 crisis.

To get you caught up and help understand what the hell is going on with this mess of a primary, we have to examine three things: where the primary stands now, what the heavily shuffled primary schedule looks like going forward, and the controversies still broiling over the primaries held on March 17.

The Present: Joe Biden has a very large, likely prohibitive lead over Bernie Sanders.

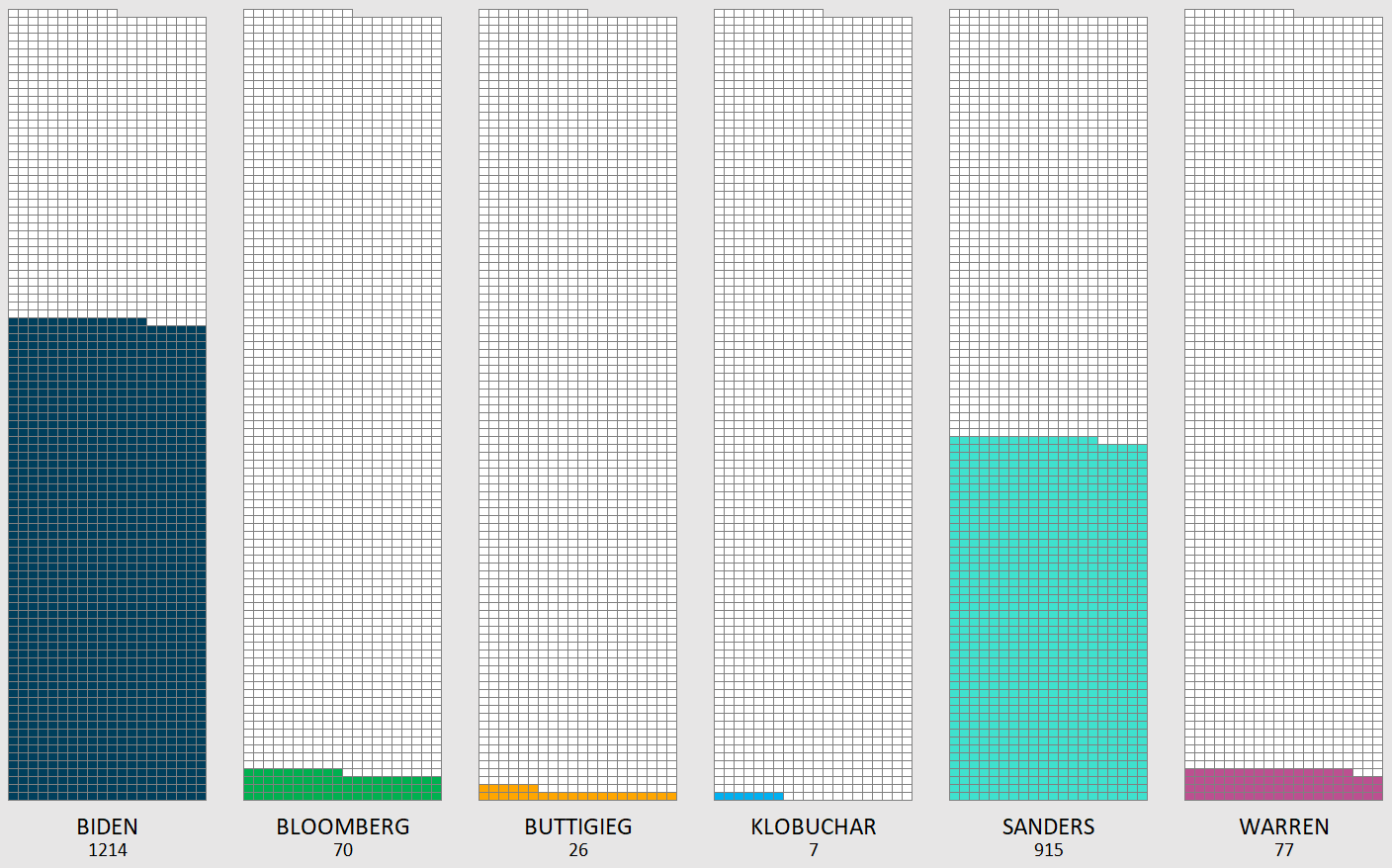

The chart below is a visualization of the current delegate count of the primary, with the latest numbers from the Arizona, Florida, Illinois, and Democrats Abroad primaries. To avoid a brokered convention and win the nomination outright, Biden or Sanders must win at least 1,991 delegates. Each square above the candidates’ names represents one delegate. Squares are filled in when they win a delegate. Blank squares represent the gap between where they are now, and where they must be to secure a majority.

As you can see, Joe Biden has a 299 delegate lead over Bernie Sanders. That’s… a lot. At the end of the 2016 Democratic Primary, Hillary Clinton’s victory margin over Bernie Sanders in terms of pledged delegates (i.e. only delegates won through the primaries, and not including superdelegates) was 349 delegates.

Biden is only 50 shy of that, despite the fact that there are still something like 1,700 delegates still unaccounted for.

But that means Sanders could still catch up, right? Well, there is a problem:

It’s really hard to make up a 300 delegate deficit, and the way rounding figures into delegate allocation complicates matters.

When you’re in the back half of the race and enjoying a large lead, as Joe Biden is, you don’t have to work nearly as hard. For Biden to attain an overall majority of delegates, he only needs to win 45.1% of the remaining delegates. On the other hand, Bernie Sanders has to win 63.1% of the remaining delegates.

If we were to assume that means Sanders needs to win an average of about 63.1% of the vote, well… Sanders has fallen far short of that mark to date. Discounting the couple territorial caucuses we’ve had, which have delegate counts in the single digits and total vote counts are in the hundreds, Sanders hasn’t won 63.1% of the vote in a single state. In fact, the only states he has broken 50% in were Vermont (50.8%) and North Dakota (53.3%). And North Dakota was itself an outlier, given that while it was called a caucus, it was actually a “firehouse primary,” which is a strictly party-administered affair—states run most primaries—and voters had to travel to one of only 14 locations in the state to submit a ballot. A total of only 14,413 people voted in the North Dakota primary… caucus… whatever.

To date, Sanders’ best performance in a typical primary state, aside from his home state of Vermont, was the 42.5% of the vote he got in Idaho on March 10th. In other words, he really has to up his game a lot. But he doesn’t need to up his game to 63.1% of the vote. In many instances, he has to hit more like… 70%. Sometimes 90%.

Why? Well, rounding.

State delegates aren’t won out of a big pot. If you win 60% of Ohio’s votes, you don’t get 60% of their delegates. Delegates are broken up in 3 groups:

- District delegates: For each congressional district in a state (the level at which representatives are elected to the House of Representatives), a state gets around 3 to 8 delegates. The number of delegates a district gets depends on the number of Democratic voters in that district. The votes you win in that district determine how many delegates you get out of that district. You might dominate statewide, but if you do poorly in a district, you get very few delegates in that district. And if you get less than 15% of the vote in the district, you get no delegates.

- PLEOs: PLEO stands for “party leaders and elected officials.” These are awarded based on the statewide vote. If you get 60% of the statewide vote, you get around 60% of the PLEOs.

- At-large delegates: These are also awarded at the statewide level, so, same deal with PLEOs. Why are there two different groups of statewide delegates? I dunno, man. Political parties are strange things.

So, for Sanders to win the nomination, he needs to not only win 63.1% of statewide delegates (PLEOs and at-large d’s), but also district delegates. He can win 63.1% of statewide delegates with around that much of the vote. That’s relatively straightforward. The big problem Sanders faces is how rounding impacts the allocation of delegates at the district level.

When you have only two candidates in a primary race, calculating the number of delegates a candidate wins in a district is pretty easy: take their vote percentage, multiply it by the number of delegates in the district, and round to the nearest number. If Sanders wins 64% of the vote in a 5-delegate district, 64% x 5 = 3.2, which rounds to 3. Sanders gets 3, Biden gets 2. (There are some edge cases where a spoiler candidate can hurt one candidate and help another, but this isn’t really relevant, as even Tulsi Gabbard has quit the race.)

But do you see the problem in the above example? Sanders got 64% of the vote, more than that hallowed 63.1% figure. But he only got 3 out of 5 delegates, or 60% of the delegates. He slightly overshot the vote, but undershot the needed delegate margin.

And every time he falls short of the mark in one district, he has to do even better elsewhere. But it’s all too easy to get punished for falling just a little bit short.

To illustrate just how easy that is, we can calculate just how high a percentage of the vote Sanders can get in districts with 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 delegates, and yet fall short of the 63.1% of the delegates he needs:

- 3 delegates: Winning 49.99% of the vote = 1 delegate, or 33.3% of delegates

- 4 delegates: Winning 62.49% of the vote = 2 delegates, or 50% of delegates

- 5 delegates: Winning 69.99% of the vote = 3 delegates, or 60% of delegates

- 6 delegates: Winning 58.33% of the vote = 3 delegates, or 50% of delegates

- 7 delegates: Winning 64.28% of the vote = 4 delegates, or 57.14% of delegates

- 8 delegates: Winning 68.73% of the vote = 5 delegates, or 62.5% of delegates

There are many, many scenarios where Sanders can win more than half of the vote, or even more than two-thirds of the vote, and still end up falling short of that 63.1% goal. And every time he falls short somewhere, he has to make it up elsewhere. If he wins only 2 out of 4 delegates in one district, he has to win 3 out of 3, 4 out of 4, 4 out of 5, 5 out of 6, etc. etc. delegates elsewhere. And that’s extremely difficult. To win 4 out of 4 delegates in a district, you have to win 87.5% of the vote. To win 4 out of 5, you need 90%. Every minor shortfall requires an absolutely heroic over-performance elsewhere.

And that’s a tough gig for someone who’s best statewide vote percentage in a primary, to date, is 42.5%. If only the best were yet to come. But…

The Future: The upcoming states don’t favor Sanders at all.

Due to the COVID-19 outbreak, the schedule for the 2020 Democratic Primary is extremely fluid. More than a dozen states have changed the dates of their primaries. But regardless of the dates on which the remaining states vote, we know exactly what states are remaining. And we know exactly how Sanders performed in them in 2016.

Here are those states, and the vote share that Sanders received in each state in 2016:

- Alaska: 79.6% (caucus)

- Connecticut: 46.42%

- D.C.: 20.69%

- Delaware: 39.15%

- Georgia: 28.20%

- Guam: 40.46% (caucus)

- Hawaii: 71.48% (caucus)

- Indiana: 52.46%

- Kansas: 67.90% (caucus)

- Kentucky: 46.33%

- Louisiana: 23.18%

- Maryland: 33.81%

- Montana: 51.56%

- Nebraska: 57.14%

- New Jersey: 36,68%

- New Mexico: 48.47%

- New York: 41.62%

- Ohio: 43.14%

- Oregon: 56.24%

- Pennsylvania: 43.53%

- Puerto Rico: 37.86%

- Rhode Island: 54.71%

- South Dakota: 48.97%

- Virgin Islands: 12.88% (caucus)

- West Virginia: 51.41%

- Wisconsin: 56.59%

- Wyoming: 55.71%

Looking at the above, Sanders’ best performances were in Alaska, Hawaii, and Kansas. He dominated in those states. But there are two problems. One, none of those states have very many delegates. Two, all those states had caucuses… and none of those states have caucuses now. And as we’ve seen, Sanders has lost a great deal of ground in states which shifted from caucuses to primaries—exhibit A being Washington, where Sanders won 72.72% of the vote in the 2016 caucus, but only 36.57% of the vote in the 2020 primary.

Setting these aside, Sanders is left with states where he got anywhere from 20% to 57% of the vote in 2016. Even if Sanders were to equal his performance in 2016 in those states—which he has failed to do so far—it wouldn’t be enough. Remember that 63.1% mark, and how he has to do better than that in terms of vote share in order to get 63.1% of delegates? He didn’t do it in 2016. And he’s not doing it in 2020.

But what if the polls are off? Are the polls missing in a systemic fashion, to where he could catch up? To answer that question, we can look at what’s played out to date.

The Past: Despite the strained circumstances under which the March 17th primary occured, and that many who would have otherwise voted did not, the outcome was exactly as expected.

I suspect that many people are under the impression that the polls have been really off in the primary thus far. After all, Biden went into the Iowa caucus leading national polls, only to finish terribly both there and in New Hampshire. And then when it seemed he was already dead and gone, he crushed South Carolina and took the lead on Super Tuesday, all unexpectedly.

The issue is that polls are only a snapshot of the status quo at the moment. The polls did accurately show that Biden was weak in Iowa and New Hampshire, and middling in Nevada. As he continued to perform poorly in those states, polls began to show Sanders closing the gap in South Carolina. The status quo had shifted from “Biden is the frontrunner” to, “the first three states have shown that Biden has no shot,” and hence polls began to reflect that. But then Representative Jim Clyburn, the living embodiment of the South Carolina Democratic Party, endorsed Biden, and in a matter of days breathed new life into Biden’s base. Biden won, three candidates dropped, and we went into Super Tuesday with a completely different set of circumstances than we’d had days before. The time begin Clyburn’s endorsement and Super Tuesday (with South Carolina sandwiched in between) was only 6 days.

But since the craziness of that time, the race settled a lot, and it became much easier for polls to keep up. The polls have proven to be very good, and I’ve been able to project the subsequent primaries very accurately based on that data.

On March 10th, Idaho, Michigan, Missouri, Mississippi, North Dakota, and Washington voted. I projected that Biden would win 219 delegates and Sanders would win 133. Based on the actual vote, Biden won 213 and Sanders won 139. Very close.

But then there was March 17th, when Arizona, Florida, Illinois, and Ohio were set to vote. But in the days before, COVID-19 rapidly became a crisis. The night before the election, Governor Jim DeWine of Ohio had the director of the state’s Health Department, Amy Acton, order the polls to be closed.

There was a great deal of controversy surrounding the fact that Arizona, Florida, and Illinois ultimately opted to go forward with their primaries. Illinois was particularly impacted, as there’s relatively little voting by mail in the state.

And yet… the vote turned out as expected. I expected Biden to win 301 delegates, and Sanders 140. Biden ended up winning 293, and Sanders won 148. Despite the fact that COVID-19 certainly depressed in-person voter turnout, the polls still proved to be accurate.

As I mentioned previously, the remaining states don’t look good for Sanders. Based upon polling, where available, and demographic data where it isn’t, the only two states where I have Sanders winning are New Mexico and Oregon. But I don’t think my projections there accurately reflect the current state of the race. I am reasonably confident that if Sanders pushes through to the bitter end, he will not win any of the remaining states.

I currently project that if all the states have the opportunity to hold their primaries, Joe Biden will win 2,234 delegates, to Bernie Sanders’ 1,494. And I don’t see anything that could significantly change that outcome.